For Sipps Maswanganyi, a safari guide with 20 years of experience in the African bush, it was one memorable sighting that sold him on electric safari vehicles.

“I could hear this buffalo panting heavily deep in the bushes,” recalls Maswanganyi, head guide at Cheetah Plains, a luxury outfit in South Africa’s Sabi Sands Game Reserve. Following those faint sounds, he found a 1,500-pound bovine on its last breaths being taken down by seven stealthy lionesses. “If I was in a noisy diesel vehicle I would have driven right past, not hearing a thing, and we would have missed it all.”

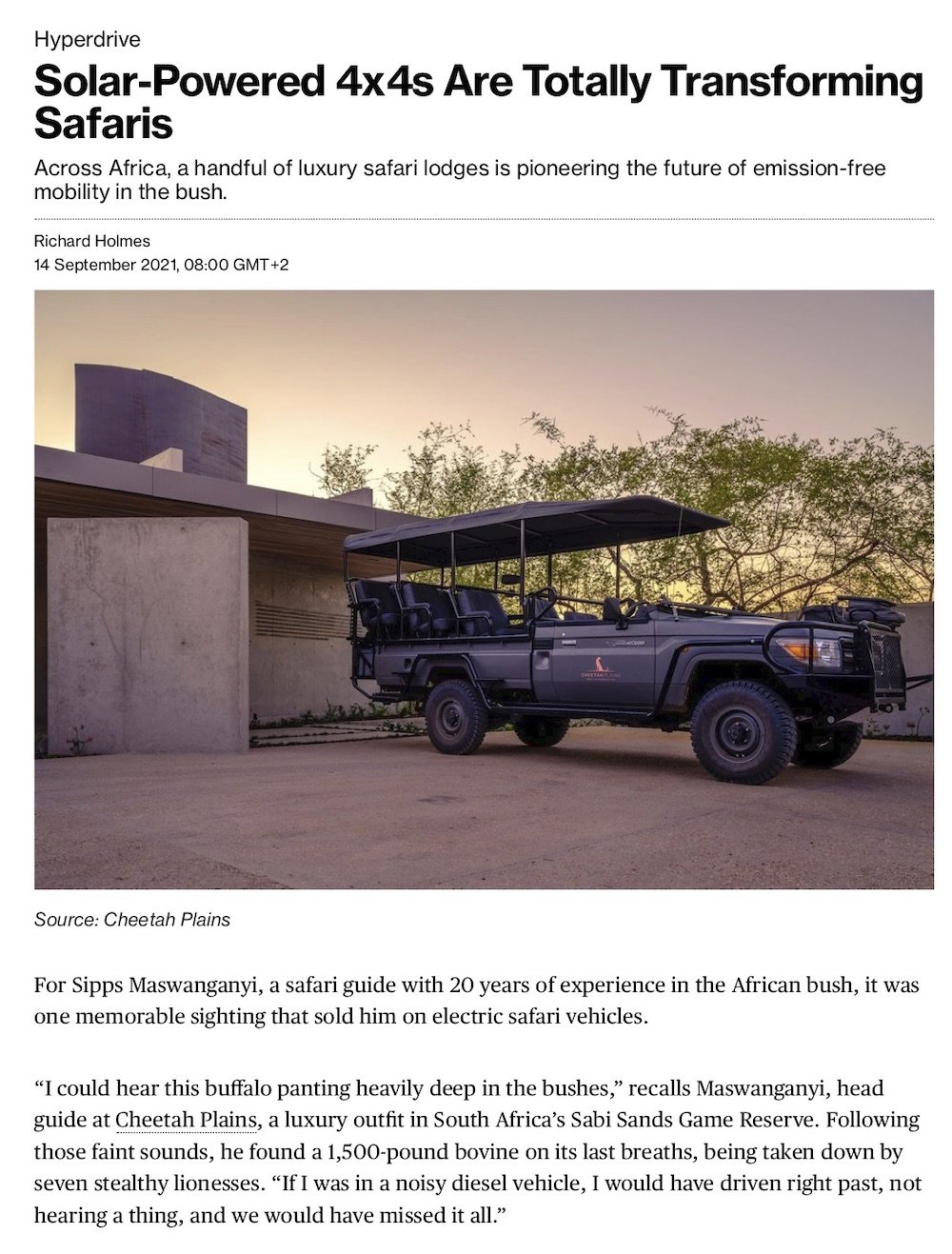

Though the diesel-hungry Land Rover chugging noisily across the African savannah is a time-honored trope of the industry, it’s an image steadily being replaced by eco-friendly whisper-quiet vehicles powered by pure sunshine.

“It was an easy decision,” says Japie van Niekerk, owner of Cheetah Plains, of the decision to offer an all-electric fleet of safari vehicles. “They are silent. They’re low on maintenance. And there are huge logistical benefits, as we don’t have to deliver fuel to the lodge out in the bush. But more than that, it’s the right thing. We are guests in nature, so why leave a footprint when we can be silent and blend in?”

Van Niekerk is just one of a rough dozen early adopters, which since 2014 have begun ditching their diesel engines. But with the technology becoming more affordable and more safari outfitters doubling down on greening their operations, the trend—which transforms the safari experience for guests—is finally gaining traction.

Disrupting the Disruption

For wildlife enthusiasts, the metallic rattle of a diesel engine can feel like an exhilarating sound—proof of an adventure—until it literally spooks the herd of red lechwe that were about to become supper for a lurking leopard. With the help of electric vehicles, even birders can silently reposition for better views without scaring off a dream sighting. There’s an entire bushveld chorus that most people miss out on, listening to that mechanical hum instead.

But making the switch to electric vehicles has been a challenge for the safari industry. While the hardware has been widely available for decades, electric motors capable of driving heavy off-road vehicles draw plenty of power, and battery technology has only recently become efficient enough to meet those needs. That, combined with lower cost and a growing awareness around sustainable travel, has created the perfect opportunity for solar-powered safaris to hit the proverbial gas.

Today’s electric safari vehicles (ESVs) are typically rebuilt Land Rover and Toyota Land Cruisers, the diesel-driven standards of the safari industry. Private companies in South Africa and Kenya are responsible for most conversions, replacing the engine, gearbox, and combustion components with an electric motor, batteries, and control system. The extensive retrofit often allows for more whimsical upgrades too, from in-built seat-warmers to USB charge points. The process costs $35,000 to $45,000 per vehicle.

That’s a substantial investment even for the largest safari operators in Africa—explaining why the likes of andBeyond, Singita, and Wilderness Safaris have yet to introduce ESVs into their fleet.

“In time we will convert to electric vehicles,” explains Dr. Andrea Ferry, Singita's group sustainability coordinator. “The reason we’re not there yet is simply about priorities,” she adds. “Right now it’s better to spend our available funds on renewable energy.”

With 67 game vehicles across its lodges in East and Southern Africa, Ferry says that converting its fleet would cost around $3.5 million dollars. That’s the equivalent of 1,400 bed-nights at current rates—money she argues is better spent on taking lodges off the national grid and onto solar power.

“There’s no point having an electric vehicle charged by a coal-driven national grid. You need to be on solar, and charge the vehicle on solar,” agrees Tony Adams, Conservation and Community Impact Director at andBeyond. “Electric vehicles are phenomenal in terms of guest experience, but our focus is on the work we’re doing in the communities, converting onto solar, and the reduction of our overall carbon footprint.”

The Economic Upside

For lodges with sufficient solar capacity and capital to spare, electric vehicles offer their economic advantages.

Converting the three Land Cruisers at Emboo River in Kenya's Maasai Mara National Reserve cost $105,000, an expense co-founder Valery Super estimates will be recouped in three years thanks to lowered operational costs. At Ol Pejeta lodge in northern Kenya, Asilia Africa is trialing a single ESV and already counts savings of around $8,000 per year in fuel and maintenance. And Chobe Game Lodge in northern Botswana has had such success with ESV jeeps, it’s also invested in electric boats.

“Since we went electric [in 2014] the vehicles have saved close on 50,000 liters of diesel and the boats have saved 50,000 liters of petrol,” says Chobe’s marketing manager Andrew Flatt, who estimates the lodge recouped its initial investment in four years.

Capability isn’t a concern. Electrical components in modified safari vehicles are surprisingly rugged, with sealed engines allowing guides to ford rivers and wade through deep sand, just as they would with a traditional combustion-driven vehicle.

“In the beginning I was worried about torque,” says Maswanganyi from Cheetah Plains. “You wonder if you’re going to get stuck in mud or deep sands—but after three years we’ve never had a problem.”

Super, from Emboo River, goes one further: “We’ve been using these to tow stuck diesel vehicles out of the water!” she laughs.

A Better, Greener Safari

All that means guests won’t be limited in where they can go—much less what they can see. While early conversions suffered from range and recharging issues, current ESVs manage around 100 kilometers [62 miles] on a single charge, roughly twice the distance of your average game drive.

And the benefits are tangible. Beyond the sustainability street-cred and the ability to silently cruise into wildlife sightings, Maswanganyi says that “Without the noise of a diesel engine you can really connect to your guests and to nature.”

As it turns out, even he has been surprised by some of what he’d been missing under the roar of his engine all this time. “You can hear the hyenas call while you’re driving,” he explains. “And on some nights,” he continues, “you can even hear porcupines walking through the bush.”

This article was first published on Bloomberg.